‘The house reeked of turpentine and toast.’

Read this guest blog written for The Floating Circle magazine for the Royal West of England Academy of Art. I take a look at a painting called ‘Henrietta’ by Vanessa Bell and uncover the tragic and bohemian life of the subject and the close links to The Bloomsbury Group and life at Charleston farmhouse.

From the collection

The collection at the Royal West of England gallery is home to some incredible artworks, including a handful of works by one of our most notable British painters; Vanessa Bell.

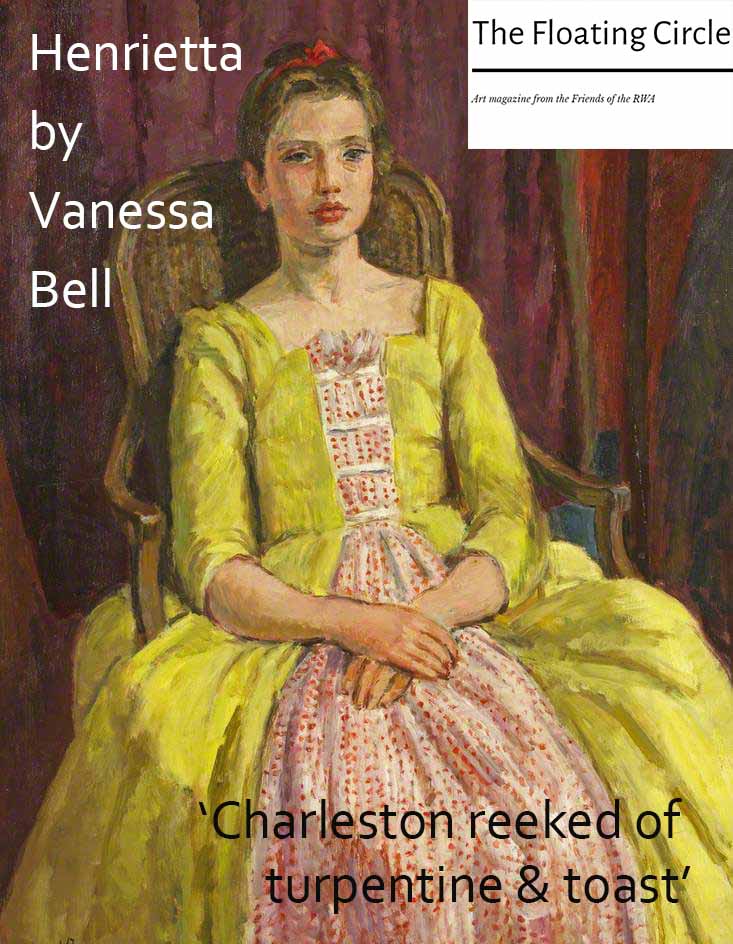

‘Henrietta’ was acquired in 1961 from the private collection of Henrietta Garnett, the granddaughter of Vanessa Bell. Vanessa would have been seventy six when she painted the ten year old girl at Charleston farmhouse. Henrietta is a beauty with her bee-stung lips and symmetrical features, right on the cusp of womanhood. The innocent gaze and prim yellow dress hide the many complications of her unconventional family upbringing, with the added pathos of knowing the somewhat tragic life that followed. Shockingly, within seven years of this painting, Henrietta would be a teenage widow with a tiny baby to care for.

The life of Vanessa Bell and her sister Virginia Woolf is well documented in their novels, artworks, biographies, films and at her family home; Charleston. But less is known about the generations that followed the famous Bloomsbury Group – those who were brought up in the shadows of these trailblazers found it hard to carve out their own identity.

Who is Henrietta?

Henrietta was no exception. Born in 1945 one of two daughters of Angelica and David Garnett, the former lover of Duncan Grant. Grant lived with Vanessa at Charleston for over forty years and fathered Angelica illegitimately – it was only on at eighteen years old that she learnt of her true parentage, always believing her father to be Clive Bell. Despite their twenty year age gap, and Garnett having once been in love with Grant, they parented Henrietta and Amaryllis. It was amid these complex affairs that life began and continued throughout her adult life. It is no exaggeration to say that suicide, early death, homosexuality, open marriages and extra marital affairs touched the lives of every member of this family.

Although brought up at Hilton Hall, a cold Jacobean house, Henrietta spent many holidays at colourful Charleston where she sat for many portraits – this one shows her in more formal dress than in others, but often in the same interior setting. Bell experimented with complete abstraction in 1914/15 but continued to paint with a figurative element after moving to Charleston in 1916. She often drew inspiration from her domestic life, and family members, which particularly suited her in old age as she rarely left Charleston.

She was ‘the apple of her grandmother’s eye,’ and described being painted by Bell with incredible detail, ‘mixing the colours on the palette, glancing first at me and then at the portrait, gently stabbing the canvas…the glances she sent across the room were extraordinarily intimate and reassuring: an observant nod, an amused smile.’ (Taken from an excerpt written by Virginia Nicholson on the Charleston website https://www.charleston.org.uk/henrietta-garnett/)

Influences of the post impressionists

The composition of this painting is simple and the colours bold. Even though she has flattened the pictorial space, there is definitely a feeling of movement as if Henrietta might stand up and walk away at any moment. One can certainly see the influence of the post impressionists such as Cezanne or Gaugain in her colour choices and expressive brushstroke. Bell had travelled in Europe visiting Picasso’s studio before spending time in Paris. She was present at the groundbreaking Post-Impressionist show curated by Roger Fry in 1910 and it influenced her work every day beyond.

Bells began using colour in a grey, post war Britain (1916) which was totally unique at the time and continued to explore a bold palette throughout her career. Some say this love of colour was a reaction to an early encounter with John Singer Sargent, her tutor at The Royal Academy who didn’t agree with her ‘overuse of grey’.

She took his advice literally and consequently painted objects, furniture, lampshades and textiles with colour. Her home was an eclectic mix of Indian textiles, books, sculptures, Matisse and Picasso’s hung on the walls – even her gardens were planted with clashing borders. If you visit Charleston today, you will see the nude figures painted across the fireplace, walls, doors…colour and pattern on every surface. This is the bohemian world of Charleston that Henrietta would have experienced, ‘It was an extraordinary treasure chest overflowing with familiar curiosities, beauty, ideas, people and jokes. It reeked of turpentine and toast, of apples, damp walls and garden flowers. The atmosphere was one of liberty and order.’

Henrietta only learnt of her complicated inheritance in a memoir written by her mother, Deceived with Kindness (1984) just as she herself was about to get married. At only seventeen years old she married Bruno Partridge, the son of Ralph and Frances (the sister of David Garnett’s first wife, Ray Marshall) ten years her senior and family friends of her parents. A year later, their daughter Sophie was born and in the same year Bruno suffered an aortic aneurysm and dropped down dead instantaneously.

The shock of his death led to a decade of debauchery and hedonism in the swinging 60’s. She led a nightclub life in Marbella, and then drifted around Cumbria and Ireland in a gypsy caravan convoy in search of peace and love. Her life took many twists and turns sadly resulting in an attempted suicide which left her in persistent pain. She married again, twice, before finally settling down with Mark Divall who had once been a gardener at Charleston. In the 80’s she lived in France, Normandy and Provence, and then discovered her creative oeuvre with the successful romance novel ‘Family Skeletons’ (1996) – not unaware of the titles resonance. It had taken until middle age to become a success in her own right.

Quiet courage

She died last year, whilst living in Sussex, closer than ever to her literary and artistic lineage. When I look at her portrait now, I see a stoic and feisty girl. Her grandmother had a ‘lifelong reputation for defying social conventions,’ and it seems Henrietta did too. James Beechey, journalist for The Guardian writes in her obituary, ‘None of life’s vicissitudes could dent Henrietta’s bewitching beauty. She was droll, mischievous and uninhibited. She could be exasperating, a menace even, but she was also deeply affectionate and deeply loyal. Quiet courage was perhaps her most impressive quality, a stoical refusal to succumb to self-pity which she maintained till the end.’

LINK TO THE ARTICLE ON FLOATING CIRCLE MAGAZINE

To commission a feature from Sarah Edmonds, please get in touch.